Yoandy Cabrera

Democracy is a fragile creature. If there is one lesson to be learned from the Trump Administration, it is that the great freedoms and strengths of democracy can easily be manipulated against the very system that guarantees them. Freedom of speech can be used, as a shameful disguise, to defend discrimination or the most humiliating lies. This so-called ‘permissiveness’ of democratic principles can lead to a figure with no respect for truth or laws rising to power.

On the other hand, I have—more than complete certainty—a strong intuition that one of the reasons democracy emerged in Greece is the nature of its mythology. Both systems of representation (the democratic and the mythological) are characterized by their diversity, constant transformation, and openness to change. They aim to ensure order while always assimilating other possible forms and versions. Both are inclusive and contradictory, continuously questioning any leader, whether it be Agamemnon or even Zeus himself. Before democracy emerged as a form of government in Greece, all these characteristics were already present in Greek mythology. That’s why it doesn’t seem far-fetched to say that the emergence of the democratic system was preceded and, in part, influenced by the nature of classical myth.

This connection between myth, democracy, and thought should make us understand, from Greece to the present day, the importance of the humanities and philosophy for the dynamic functioning of a society that considers itself democratic. Any step against the cultivation of free humanistic thought seems to lead us closer to simplistic polarizations, authoritarianism, dictatorships, censorship, blind loyalty to a charismatic leader, and the easy manipulation of the masses.

In his text “De los mitos a la inestabilidad de la democracia griega” (“From Myths to the Instability of Greek Democracy”), Juan A. Roche Cárcel argues that “democracy has (…) an innate origin in myth (…), which connects it in an inseparable way (…) to primordial chaos and closely ties it to the essential instability of the human condition.” Moreover, for Roche Cárcel, “the creation of democracy represents a response (like that of philosophy, politics, economics, geometry, art, and tragedy) to the chaotic order of the world and a possible way out of the cycle of hubris,” which does not mean it extinguishes or nullifies it. However, the democratic system has a much more complex task than Greek mythology or artistic-literary creation, as it is called upon to establish order while striving to embrace the greatest possible diversity. Democracy upholds, facilitates, and defends the plurality of myth, thought, and creation; in this lies both its greatness and its danger.

To better understand the difference and, at the same time, the relationship between creation and democracy, I want to refer to a scene from the series Designated Survivor in the first episode of the second season (2017): the president receives the writer Elias Grandi at the White House, who has been nominated to receive the National Medal of Arts. However, the author tells him that he cannot accept the award because he abhors and opposes everything the president stands for, believes that the institutions are sick and in decline, and feels that his literary work is not something the president would agree with. But to the writer’s surprise, the president is not only an avid reader and admirer of all his novels, but also expects nothing less from him than to question the institutional order.

For the president, the government exists only as a vehicle or tool, not as an end in itself; it enables us to live, love, and create. The reason for the existence of a democratic government is to serve and make life easier for a citizen, even if that citizen is not a supporter or defender of those elected. Faced with such a response, Grandi doesn’t know what to say or do. “Keep writing,” the president tells him. The president doesn’t want the artist to stop criticizing or questioning him; quite the opposite. He doesn’t censor him for challenging him and his policies; he rewards him for putting his freedom at the service of his own thought and talent. His role, as president, is to defend the artist’s right to create and question everything, including the very government that has chosen to honor him precisely for his work, which is so critical of the system.

I believe this scene illustrates how complex, inclusive, and contradictory democracy is, as it seeks to open itself up to the rights of all. Bringing this matter into the mythological realm, one could say that democracy exists to prevent and oppose the capture or control of myth by one individual or group. The monopolization and unilateral management of myth lead to dictatorship. Democracy fosters the continuous creation of new fictions, languages, grammars, and mythologies, without imposing restrictions.

It is easy, however, for democracy and the republic to become a dictatorship. Greek democracy and the Roman Republic are themselves examples of this failure. Many modern revolutions also bear the mistake of moving from the struggle for freedom to the establishment of an exclusive and, in some cases, totalitarian system. This is the case with Cuba, for example, which clearly illustrates how the hijacking and unilateral management of national myths and fictions reflect the dictatorial nature of its government.

Athenian tragedy (whose narrative source is primarily myth) bears witness to this failure within Athenian democracy: while Aeschylus supports the new system with the guidance of his Athena in Eumenides, Euripides—who experiences the decline of the very system praised by Aeschylus—reflects in The Trojan Women the level of cruelty to which Athens descended to maintain power, imposing its authority and control over the other Greek territories of the Delian League. Therefore, to avoid its collapse, where classical mythology can allow for anarchy, democracy is called to continuously review and safeguard the boundaries between freedom and chaos. This is precisely what the system of checks and balances seeks to achieve in American democracy.

Thanks to the plural, contradictory, elastic, and inclusive nature of Greek myth throughout the ages, there is no difference between Athena’s attitude as she advises Achilles in the first book of the Iliad—the pinnacle of epic oral development from the 15th to the 8th century BCE and a representation of aristocratic power—and that of Athena who concludes Aeschylus’s Oresteia in the 5th century BCE, during the full development of democracy, even though both texts belong to different eras and systems of government.

In the first case, just as Achilles is about to draw his sword to attack Agamemnon, Athena appears, visible only to Achilles (as a sort of divine embodiment of his consciousness), to advise him against killing Agamemnon. However, she never imposes her will; the final decision rests with the hero. In the second case, Athena, representing the birth of the democratic system in Eumenides, concludes the voting by advising the Athenians to maintain the balance they have achieved, making order contingent upon the democratic condition, which is always in suspense and ever at risk.

In this way, generally speaking, in any era of Greek cultural development, whether in works from aristocratic periods or those created during democracy, even Zeus himself cannot impose his decisions or whims by force. This mythopolitical essence of Greek thought prevents power from residing solely in a single unquestionable figure, fostering plurality and continuous change. On the political level, this translates into the essence of democracy and remains a fundamental guarantee in contemporary democratic systems.

Even in the Iliad, an epic poem created for the delight of the aristocracy before the 8th century BCE, we find no unquestionable leader or god. The Iliad begins with a crisis in Agamemnon’s political leadership, and although he decides to act as he sees fit, the assembly opposes his intentions, supporting not his decisions but rather the words and proposal of the priest Chryses.

In Hesiod’s Theogony, a poem that describes the birth of the cosmos and the gods, each tyrant who seeks to perpetuate their power (Uranus, Cronus, Zeus…) is always challenged by other gods. These examples serve to illustrate how, from the earliest texts of what we call “Greek literature,” there tends to be opposition to any superior authority that claims to be unquestionable (whether divine or human), always leaving room to resist any tyrant or any form of closed domination. This stands in stark contrast to the biblical and Hebrew tradition, where the singular God is infallible, all-powerful, unquestionable, and eternal in His sovereignty.

As previously seen in Aeschylus, the figure of Athena is linked to democracy from its very foundation. The image of the goddess, daughter of Zeus, along with her various iconographic representations, accompanies the subsequent democratic development. It is no coincidence that many depictions of the Statue of Liberty (the one that welcomes immigrants in New York and also crowns the dome of the Capitol in Washington) are among the most recognized and important symbols of American democracy. There is no doubt that this reflects how the “Founding Fathers” based their own system on the Greek model. From the founding of the Thirteen Colonies to the present, for example, the independence of each state references the functioning of the polis or Greek city-state.

Myths play a fundamental role in the set of fictions and symbols that constitute what we call “nation” or “fatherland.” While it is true that the use of these myths in literature and art generally prioritizes the anarchic, the transgression, and the questioning of any control apparatus (whether within or outside of democracy), it cannot be denied that figures like Hercules, Athena, or Aeneas have traditionally been used to embody political order, even though their literary use is broader and more audacious. For example, we see the figure of Hercules in the frontispiece of the University of Salamanca, the Statue of the Republic—modeled after the goddess Athena—in the Havana Capitol, and Aeneas carrying his elderly father Anchises and bringing along his son Ascanius as a representation of the European Union in front of Palazzo Valentini in Rome.

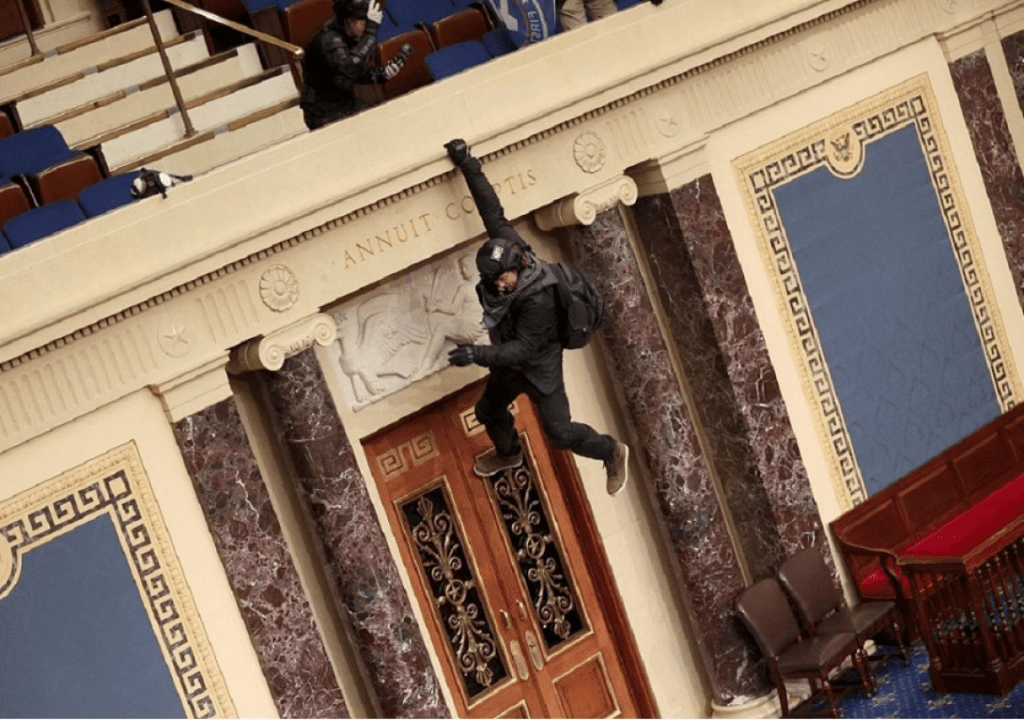

I had never before understood so clearly what is at stake on the other side of Athena’s counsel at the conclusion of the Oresteia than when I observed the images and videos of the assault on the Capitol in Washington on January 6, 2021. As happens in Aeschylus’s play, there was also a counting of votes in Washington that day, consolidating once again the functioning of the democratic system. But, unlike Aeschylus, the fans and extremists loyal to the outgoing president broke through the police barricade, smashed doors and windows, launched gas, and interrupted the system for several hours.

The scenes of violence, the injured, and the dead left by this incident provided a glimpse, albeit for a brief moment, of what it would be like to live in the United States on the other side of the democratic condition. Fortunately, the damages were manageable, and a few hours later, Congress was back in operation. The Aeschylean play in the style of American democracy was restored. It then made me think of that precarious line between freedom and chaos that democracy is obligated to safeguard and continuously review.

As Cuban journalist Ernesto Morales says, “Fortunately, this country [the U.S.] is not uniform in anything,” and that is its democratic greatness. But at the same time, this greatness carries dangers in the hands of an irresponsible president who incites his followers to storm the Capitol, which is considered the sacred space for the functioning of the democratic system. In more general terms, Roche Cárcel explains this dichotomy as follows:

Democracy, like any other human enterprise, cannot automatically guarantee permanent success, nor is it secured against itself, since its very action produces unexpected consequences. Therefore, it represents a regime of self-limitation and historical danger, of the tragic and the possible, and embodies the only form of government that must fear its own mistakes, while the others do not know risk but do know the certainties of absolutism and servitude.

If the attack on the Capitol had not been controlled in time, the damage would have been greater, even irreversible. It could have crossed to the other side of the condition suspended on Athena’s lips. Those of us who have suffered under totalitarian regimes in our countries of origin know what it is like to live on the other side of democratic conditions. Some of the violent Trumpist demonstrators had clear objectives to kidnap and attack specific politicians present in Congress during the certification ceremony of the elections held in November 2020. Like the Sword of Damocles hanging over democracy, in moments like that, one feels the echo of the words and warnings from the second American president, John Adams, in his letter to John Taylor in 1814:

Democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes, exhausts, and murders itself. There never was a democracy yet that did not commit suicide. It is in vain to say that democracy is less vain, less proud, less selfish, less ambitious, or less avaricious than aristocracy or monarchy. It is not true, in fact, and nowhere appears in history. Those passions are the same in all men, under all forms of simple government, and when unchecked, produce the same effects of fraud, violence, and cruelty.

I remember my astonishment at seeing an image of one of the instigators hanging from the second-floor wall in the Senate chamber, with his foot in the east door, almost brushing against the Latin phrase “annuit coeptis” engraved in stone, amid Greek fretwork and other classical motifs, right at the height of the frieze where it reads “patriotism,” featuring a relief of the eagle and the figure of the worker with a sword in hand, ready to defend his country.

Seen in the same plane, between the citizen sculpted in the relief and the Trumpist vandal, one can observe the ongoing tension that exists between freedom and chaos within the democratic system. This tension is compounded by others: the Latin phrase “annuit coeptis,” which also appears on the Great Seal of the United States and the reverse of the U.S. dollar, is often translated as “He has justified the enterprises I have undertaken” or “He has said yes to the enterprises we carry out.” This phrase is a version of part of verse 625 from Book IX of the Aeneid, the epic poem by Virgil.

The complete line says, “Iuppiter omnipotens, audacibus adnue coeptis” (“Almighty Jupiter, approve these bold enterprises!”) and is the beginning of a prayer from Ascanius (son of Aeneas and grandson of Aphrodite) asking for Jupiter’s favor before shooting in the midst of a battle, in the territory that will one day become Rome and the beginning of the Roman legacy. Note the grammatical variation of the Virgilian phrase in the Great Seal of the United States: it has shifted from “adnue coeptis” (in the imperative or prayer form in the original Virgil text) to “annuit coeptis” (in the past tense, indicating that the enterprise has already been granted).

We move from the prayer for enterprises in Virgil to assuming them as granted in the American democratic chamber. That one of the Trumpist assailants hangs in the most essential democratic space undoubtedly exposes the imbalance, the sometimes blurred boundaries, and the crises to which democracy can sometimes be subjected. Many of the rioters who violently stormed the Capitol on January 6, including the one hanging in front of the “patriotism” relief, consider themselves “patriots.” This illustrates how certain nationalist extremisms, or any other type, are closer to dictatorial than to democratic. The Athena/Freedom that crowns the Capitol in Washington, as well as the one inside the building, serve as reminders of how easy and dangerous it is to slip from freedom into chaos, not to forget that all democratic guarantees are fragile, conditional, and always on the verge of being lost. They depend on the continuous balance of the tragic and the possible.

Leave a comment