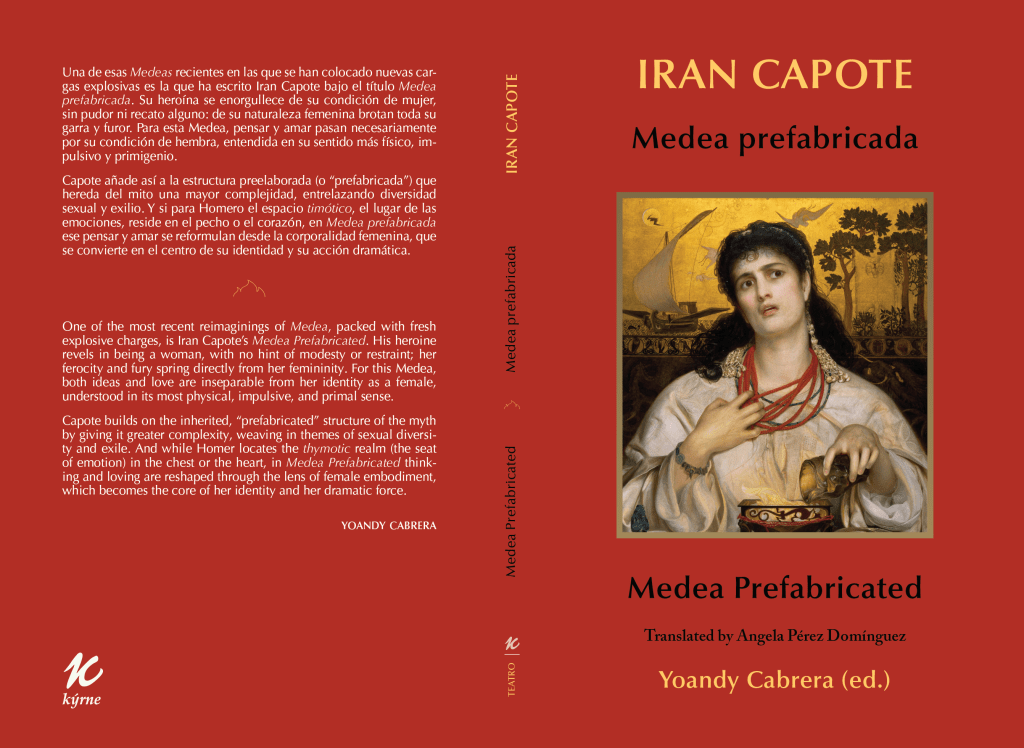

Yoandy Cabrera

Photo by Todd Rosenberg

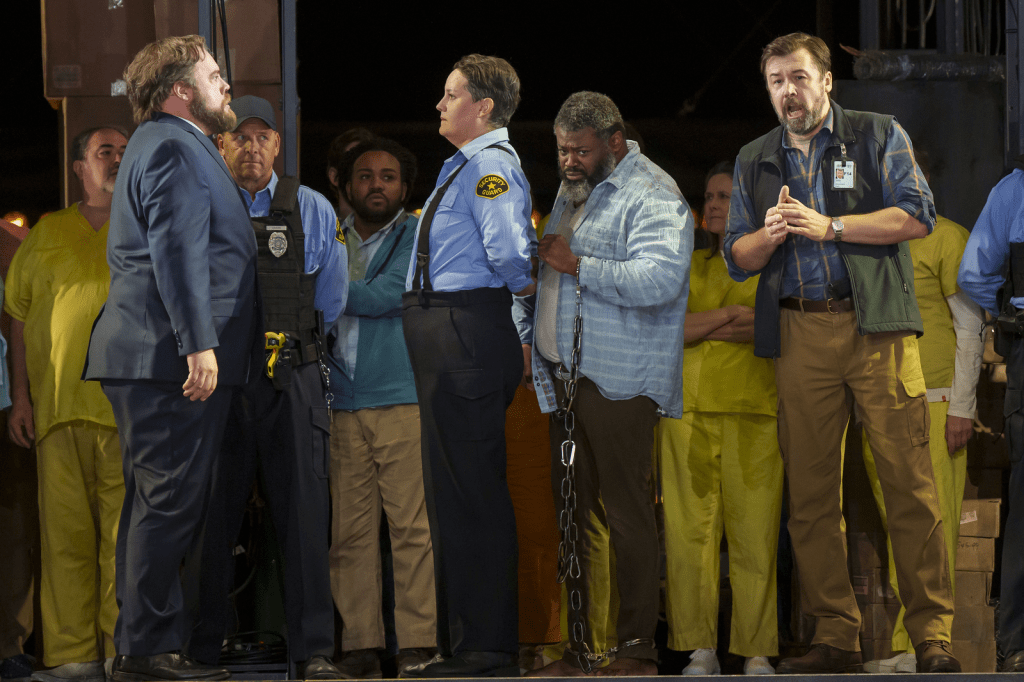

Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio, composed in 1805—more than 200 years ago—is presented as a new production by the Lyric Opera of Chicago from September 26 to October 10, 2024. I attended the performance on Sunday, September 29, 2024. This version, directed by Matthew Ozawa and conducted by Enrique Mazzola, is set in a contemporary context, encouraging audiences to reflect on where justice resides and what forms of tyranny and dictatorship may be emerging in our societies today. With its uplifting conclusion, this hopeful work celebrates humanity’s ability to overcome oppression and defeat tyranny.

Beethoven was born in 1770 in Bonn, Germany. By the late 1790s, in his twenties, he began experiencing hearing difficulties. In 1801-02, he went through a period of deep crisis. Although he never married, his only opera centers on conjugal love intertwined with political themes. It may have been his sole operatic endeavor due to the challenges of composing an opera while struggling with advancing deafness.

Photo by Todd Rosenberg

Fidelio is believed to be based on a real event during the French Revolution when a woman rescued her husband from prison. Jean Nicholas-Bouilly used this incident as the basis for his libretto Léonore, ou L’amour conjugal, which was staged in Paris in 1798. Joseph Sonnleithner and Friedrich Treitschke later adapted this work for Beethoven’s opera. Setting the story in no specific place or time may have been a strategy to avoid censorship and political repercussions. This timeless quality also allows modern directors the flexibility to present the opera in various contexts or historical periods, including contemporary settings.

Fidelio/Leonore (performed by the South African-born soprano Elza van den Heever), a woman disguised as a man, works in a prison to find her husband, Florestan (interpreted by the celebrated American tenor Russell Thomas), who has been unlawfully imprisoned by his enemy, Governor Pizarro (performed by Brian Mulligan). Pizarro plans to eliminate Florestan, but Fidelio/Leonore is prepared to fight the governor if necessary to save her husband. The opera concludes with Pizarro receiving his deserved punishment, and Florestan and Leonore praising the power of conjugal love.

Russell Thomas as Florestan, and Dimitry Ivashchenko as Rocco

Photo by Todd Rosenberg

According to Director Ozawa in his program note, Fidelio has long been regarded as “a symbol of hope for generations of people afflicted by oppression.” It was revived in 1814 as a statement against Napoleon’s autocratic tyranny and performed in 1937 and 1941 to condemn Europe’s Nazi terror. In 1954, performances of Fidelio also served as a protest against Stalin’s regime following his death in 1953.

The title, with its masculine name, is both playful and ironic, as Fidelio is, in fact, Leonore in disguise. This element introduces the potential for a love triangle and confusion, reminiscent of characters from classical tradition (such as Achilles and Hercules), the Italian Renaissance, and the Spanish comedia of the early modern period.

Photo by Todd Rosenberg

In her program article, Professor Martha C. Nussbaum highlights how, at several points in the opera, ordinary moments and routine situations elevate to the sublime, transforming common people into more reflective and spiritual beings. This perspective offers a meaningful way to understand the so-called “ordinary” moments in Beethoven’s work—those sometimes viewed as dramaturgical pauses or evidence of the composer’s inexperience with opera. Any ordinary person or action can ultimately embody a heroic deed, and any routine context can become the starting point for a more profound, transcendental situation. Fidelio evolves from what may initially seem like a light comedy (during the first 30 minutes) into a complex, challenging, and darker drama as the opera progresses.

The prominent role of the orchestra in this opera makes Fidelio unique within the operatic tradition. The most significant musical elements rely heavily on the orchestra, as Fidelio follows a symphonic structure, reflecting Beethoven’s inclination towards instrumental composition. Additionally, the Prisoners’ Chorus is symphonically conceived. In her article, for instance, Nussbaum draws a parallel between the finale of Fidelio and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

Photo by Todd Rosenberg

As a Cuban, it is difficult for me not to see Florestan as a symbol of the many Cuban political prisoners who are silenced today for their direct opposition to tyranny. This ongoing conflict, which gained renewed visibility after the massive demonstrations in July 2021 on the island, has persisted since the beginning of the Castro regime in 1959. For now, Fidelio offers a more hopeful resolution than what we have seen in Cuba over the past 60 years, where couples confronting the totalitarian system have often had no choice but to leave their home and country to survive.

Photo by Todd Rosenberg

Among the singers, California-born soprano Sydney Mancasola (who played Marzelline, the daughter of Rocco) delivered an organic and superb performance. Russian bass Dimitry Ivashchenko (as Rocco, the prison warden) portrayed a character navigating both the prison and political realms, caught in a cycle of corruption and straddling the blurred lines between survival and morality. In contrast, Pizarro’s portrayal in this production leaned a bit too heavily into caricature. The Cuban-Dominican tenor Daniel Espinal, a national winner of the 2024 Metropolitan Opera Laffont Competition, portrayed Jaquino with both grace and vis comica.

Photo by Todd Rosenberg

In this production, the overture features the image of Fidelio/Leonore projected onto a black curtain, alternating between the wife and the disguised prison guard. However, more space was needed for the moment when the prisoners emerged to breathe fresh air in the garden, as they never truly left the prison area for this pivotal choral scene. At times, the large number of prisoners and other characters created some confusion. Nonetheless, there was generally effective use of space, with most characters knowing where they needed to be. This production notably included imprisoned children, which may reflect political decisions regarding the children of migrants during the Trump administration. The stage design featured a rotating structure that represented both offices and prisons. Additionally, technology and screens were employed to depict torture, as well as to illustrate Florestan’s vision of his wife Leonore appearing as an angel to save him.

Photo by Todd Rosenberg

In an opera featuring outstanding duets between the main characters and several emotional choral moments, marriage is portrayed as a means of loving not only one’s partner but also the stranger that partner can become. Through her journey and suffering, Leonore learns that her husband Florestan, as a prisoner, could be anyone. In searching for her beloved, she becomes increasingly altruistic, and, ideally, we as spectators experience a similar transformation.

Leave a comment