Yoandy Cabrera

We currently live in a world where Vladimir Putin has engaged in an ongoing war against Ukraine since February 2022, the United States is approaching an election process where the figure of a “charismatic leader,” fanaticism, and ideological polarization appear to overshadow any other potential candidate and Cuba remains under the longest dictatorship in the Americas, now ruled by a deceased “Commander in Chief.” In this context, staging Exit the King by Eugène Ionesco serves as an excellent exercise to contemplate the current leaders and those who allow them to lead. As Rosette C. Lamont points out, “the more one reads Ionesco, the more prophetic his plays appear” (152).

Exit the King is one of those plays that questions absolutely everything. It shifts from denouncing and ridiculing the tyrant who considers himself eternal and irreplaceable to eliciting empathy for the same tyrant who ultimately becomes disoriented, old, forgetful, and lost. As Juliette, the kingdom’s maid, reminds us, “He’s just like us and not unlike my granddad!” (Ionesco 1967). Like most dictators, his disappearance heralds the destruction of all subservient structures. King Berenger I is “confronted with the inevitability of his own personal death, the demise of power, the end of all things” (Wright 435). The king himself will express his desolation:

KING: …like an actor on the first night who doesn’t know his lines and who dries, dries, dries. Like an orator pushed onto a platform who’s forgotten his speech and has no idea who he’s meant to be addressing. I don’t know this audience, and I don’t want to. I’ve nothing to say to them. What a state I’m in! (Ionesco 1967)

As someone born in Cuba, hearing the title of this play reminds me of the 2015 production of the same play in Havana City, which led to the Cuban government censoring and canceling the theater and film director Juan Carlos Cremata. Ionesco’s king could have appeared too similar to Fidel Castro, who was then ill and passed away just one year later. After being coerced into signing a document that prohibited him from staging any future plays, Cremata ultimately left his homeland in 2016. “I chose exile because I was fleeing from a nightmare,” he stated (Costa).

This play, therefore, serves as a way to denounce dictatorial behaviors while also reflecting the experiences of those living under a dictatorship or following a populist or tyrannical leader. In Exit the King, for example, the doctor initially serves to please his Majesty but, eventually, he turns against the monarch, stating that “it’s all his fault! He never cared what came after him. He never thought about his successors. After him the deluge. Worse than the deluge, after him there’s nothing! Selfish bungler!” (Ionesco 1967). Except for Marguerite, who becomes a sort of Mistress of Ceremonies for the total destruction of the kingdom, most of the characters transition from devotion and dedication to repulsion and reluctance.

This play also raises a pertinent question for both royal subjects and the general public: How do we allow a dictator, a charismatic leader, a politician, or a populist to define and shape who we are while we remain silent or merely express what is expected of us?

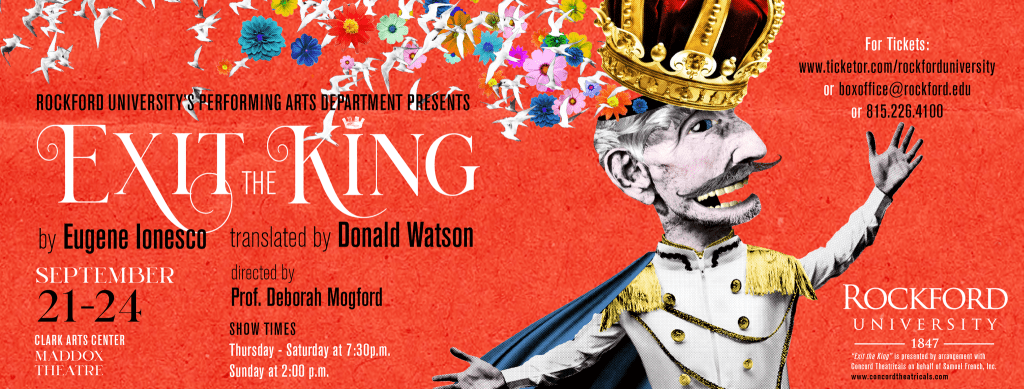

With this staging at Rockford University, under the direction of Professor Deborah Mogford, we are likely to find ourselves laughing heartily as Ionesco’s king refuses to accept the idea of impending death. Our laughter will also be provoked as the characters discuss numerous atrocities and radical decisions that doctors and soldiers have accepted and carried out, such as when the doctor says to Marguerite: “Execution, your Majesty, not assassination. I was only obeying orders. I was a mere instrument, just an executor, not an executioner. It was all euthanasia to me. Anyhow, I’m sorry. Please forgive me” (Ionesco 1967). However, the king will justify these actions as being “for reasons of State” (Ionesco 1967).

We encounter a related idea in Ionesco’s Macbett: “No. No regrets. They were traitors after all. I obeyed my sovereign’s orders. I did my duty” (Ionesco 1960). In a way, we will find ourselves laughing at what has been happening in the world since the dawn of civilizations, from the earliest empires to the present day. That is why Ionesco’s king represents not only all kings and tyrants but also every individual. The humor we find in his absurd actions and speeches is deeply intertwined with our daily lives. As Professor Mogford expresses in her note to the program, “Ionesco explored the serious issues of life through the lens of comedy.”

One by one, the characters in this play begin to realize that the king is just like them—a common human being. He was never special or immortal. As the doctor puts it, “he’s always lived from day to day, like most people” (Ionesco 1967). In this process, for the first time in centuries, the king becomes interested in his maid Juliette, savoring every moment and appreciating the tiniest details, including the beauty of a carrot:

(…) by listening to her tale of woe, the spoiled man, who thought of himself as the center of the world, reaches the knowledge that the most modest of existences is far better than no life at all. He discovers that he ought to have paid attention to simple things, such as breathing, moving, walking. He learns from this natural Zen master the lesson imparted by the ghost of Achilles to Odysseus when the latter visits the Underworld: “Don’t bepraise death to me, Odysseus, for I would rather be a plowman to a yeoman farmer on a small holding than lord paramount in the Kingdom of the Dead. (Lamont 156-57)

What initially appeared as a “metaphysical farce” and a highly modern and innovative piece (in the opening moments of the performance) transforms, in the second part of the play, into a “sublime amalgam of the tragic and the comic, the philosophic and the poetic” (Lamont 161). This metatheatrical work masterfully (re)creates a mythological and tragic journey:

If we, the audience, started the evening by laughing at a pompous, self-involved, self-indulgent man, the smile quickly fades from our lips as we realize that Berenger Ier’s fate is our fate too. Eventually, he gives up his useless thrashing and, with nobility, stares into the face of death. Thus, we discover that this farce is a classically structured tragedy, and that Ionesco, the former prankster, is one of the great classical writers of our century. (Lamont 162)

I have always been fond of and a fan of our talented Performing Arts students. Isaac Urbik exhibits exceptional skill as a guard on stage, effortlessly balancing seriousness and humor while maintaining a sense of distance yet remaining intimately connected with the audience. I cannot help but wonder if he has ever taken on a role other than Ionesco’s guard, as he fully immerses himself in his character with passion and joy, living it second by second. In her portrayal of Juliette, the maid-of-all-works, Caitlin Dennis captures a blend of exhaustion, indolence, common sense, and ease in her performance.

Robbie Strader, in his interpretation of King Berenger, exhibits flair, nerve, and poise. This character has provided Strader with an opportunity to showcase his dramatic flexibility and adaptability. The king is simultaneously pathetic, cynical, funny, and disgusting. Strader skillfully navigates the different stages of the king’s emotions after being informed of his impending death: first denial, then anger, bargaining, depression, and finally acceptance. In her analysis, Rosette C. Lamont explains that the king

must learn to travel from the space of life to the space of death. This also suggests the way of the neophyte of the Orphic cults, led into the Netherworld by a mystagogue. The women surrounding him could be Demeter, Persephone, and Tyche (the goddess of fortune). The doctor might be said to play the role of Lord of the Abyss. Ionesco echoes here many Occidental and Oriental myths. (156)

Lucy Parlapiano’s portrayal of Queen Marguerite is, from my perspective, the most critical figure in this play. She is the sole character who appears to grasp the hidden meaning of what has been unfolding from the moment she enters. Dressed as a Renaissance queen or Madonna, she also symbolizes an empty future, the voice of human conscience, and the last possible voice we hear before everything fades away. As Rosette C. Lamont observes, “whereas Juliette brought him in touch with himself and the world’s reality, Marguerite guides him to Nirvana” (160). Initially appearing to oppose the king, Marguerite is, in fact, the one who aids him on his journey towards nothingness. She, akin to the figure of the goddess Demeter, restores the king’s humanity in his utter vulnerability. Following Queen Marguerite’s final monologue, all that remains is a spaceless universe:

The old queen, seemingly a shrew, emerges as an archetypal figure, an anima embodying the instinctual world of the unconscious. She is an avatar of Demeter, the goddess of transformation. While Berenger was a young man, he was surrounded by a magical whole, Demeter and Kore. Their conjunction represents the Eternal Feminine, a guarantee of fertility and the survival of life. Now that Kore (Queen Marie) has vanished underground, the King is left with Demeter. She is the Dark and Terrible Mother. (Lamont 159)

Parlapiano, in her portrayal of Marguerite, patiently waits for the final moment when she can assist the king in accepting the inevitable. She tries to maintain her patience while interacting with others and their ignorance, yet her human emotions often break through. This struggle persists until she is alone with the king. This play isn’t just about the king’s journey towards acceptance of his impending death; it’s also about Marguerite’s transformation into an iconic figure—the Eternal Feminine, a reminder that power, dictatorship, and war are often “a lot of fuss about nothing” (Ionesco 1967). Parlapiano’s performance has allowed me to appreciate every moment of her interpretation, which is sharp, rich with nuances and contrasts, perfectly complementing the character of Marguerite.

Queen Marie is brought to life by Piper Burney. Merely having seen Burney’s previous performance as Little Becky Two-Shoes in Urinetown, and now witnessing her portrayal of Marie, is sufficient to recognize the impressive breadth of her acting abilities. Her interpretation of Marie is both refreshing and exasperating, charming and vexing. Observing the growth and development of students like Burney, semester by semester, is truly an amazing opportunity.

In this production, the character of the doctor is skillfully portrayed by three actors: Kayleigh Ferguson, Elijah Lowry, and Emmarie Wilson. Together, they have managed to maintain the action, the dynamics of the situations, and the absurd humor of the play moving in the right direction. This trio of doctors, acting in unison, represents the entirety of the kingdom’s scientific knowledge, all subjected to the whims of the king, including the task of executing others.

I used to have reservations about whether Emmarie Wilson could effectively portray a character like the doctor, as I had considered her particularly skillful at interpreting specific character types. For instance, her recent portrayal of Gwendolen Fairfax in RU’s production of The Importance of Being Earnest was brilliant. However, any doubts I had about her ability to extend beyond those roles have been completely dispelled by her performance in Exit the King. She has proven her versatility and talent in this production.

The Stage Manager for Exit the King is Kaitlyn Tesdorff, and Carter Coryell serves as the Assistant Stage Manager. Observing their work during the rehearsals reaffirms just how professional and dedicated every staging process is at RU. Additionally, this play marks the RU debut of scenic design by Eric Brockmeier and costume design by Ryan Moller, both being the department’s newest professors. Their creative concepts align seamlessly with the dynamic and dramatic progression of Ionesco’s theatrical work.

The Performing Arts program at Rockford University is distinguished by its exceptional quality and the dedication of its crew. I have never been disappointed by any play I have had the pleasure of witnessing at RU. The staging of Exit the King upholds this tradition of excellence, and it is a source of immense pride for me to be associated with RU. As a friend of mine recently commented, after accepting my invitation to attend the play, one can find good theater presentations in many small-town theaters across the country. Fortunately, Rockford University is one of those places outside of major cities where you can experience such exceptional performances.

Works Cited:

– Ionesco, Eugène. Exit the King. Translated by Donald Watson. Grove Press, 1967. Digital Edition.

—. Macbett. Grove Press, 1960. Digital Edition.

– Lamont, Rosette C. Ionesco’s Imperatives. The Politics of Culture. University of Michigan Press, 1993.

– Costa, Tania. “Entrevista al cineasta cubano Juan Carlos Cremata: ‘Vine al exilio huyendo de una pesadilla.’” CiberCuba. March 6, 2021. https://www.cibercuba.com/noticias/2021-03-06-u192519-e192519-s27061-entrevista-al-cineasta-juan-carlos-cremata-hollywood.

– Mogford, Deborah. “Not From the Director.” Exit the King’s Programme. Rockford University’s Performing Arts Department. September 21, 2023.

– Wright, Elizabeth G. “The Vision of Death in Ionesco’s Exit the King.” Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal. Vol. 54, No. 4 (Winter 1971), pp. 435-449.

Leave a comment